In July 2022 we welcomed people to Bristol and online around the world to our Mendel at 200 conference. For those who joined us face-to-face, there was an opportunity to visit the historic Bristol Zoo Gardens. George Davey Smith shares the story of some of the early zoo residents and how they relate to Mendel’s discoveries.

The 20th July 2022 was the bicentenary of the birth of Gregor Mendel – the so-called “father of genetics”. We marked the occasion by holding a two-day (20th-21st July) meeting at Bristol Zoo, with a stellar cast of internationally recognised experts in the history, ethical discussions and latest research building on Mendel’s work.

The meeting was held at Bristol Zoo, the world’s oldest provincial zoo, which opened in 1836, when Gregor Mendel was only 14. It provides a glorious setting for such a meeting, and also played a part in an international Mendelian drama.

In 1963 the zoo acquired two white tigers – Champak and Chameli – bought from the Maharaja of Rewa for more than £100,000 in today’s money. These extraordinary animals – the only ones of their type in Europe – increased the attendance figures, and by 1970 the zoo held one third of the captive world white tiger population. At this time each tiger was valued at around £200,000 in today’s money. But where had the tigers come from, and what is the link with Mendelism?

The Bristol Zoo white tigers came from a lineage that was established in captivity by the Maharaja of Rewa, then a princely state – and now part of Madhya Pradesh – in India. They had been seen in the wild around Rewa for half a century, but were not true albino tigers, having brownish stripes on an off-white background and blue eyes (true albinos lack any pigment, have pink eyes and are snowy white all over). The Maharaja named the white male tiger cub he first obtained Mohan. He kept Mohan with an orange (i.e. normally-coloured) tigress, Begum, who, in three litters, gave birth to 10 normally-coloured cubs. Mohan mated with one of his daughters, Radha, resulting in 14 offspring, some white and some orange.

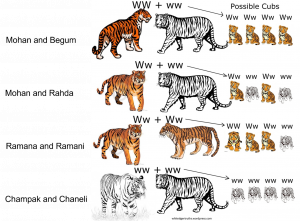

Mendel famously crossed peas with different features – including having yellow or green seeds – to demonstrate the regularities in heredity that now bear his name. Using contemporary terminology and interpretation, white tigers can be used to illustrate these regularities. Mohan must have received a copy each of the same allele (labelled w in the figure below) from his mum and his dad. At each location in the genome, individuals have two alleles. When germ cells (sperm and ova) are formed, it is a matter of chance which allele ends up in each germ cell. Begum had two orange (W) alleles; she and Mohan can be referred to as homozygous for the coat colour trait. All of their offspring would thus have a w from Mohan and a W from Begum, be designated Ww and referred to as heterozygous at this locus. W is the dominant allele, thus all the offspring were orange coloured, as in the first row of the figure below. When Mohan mated with his daughter Radha (second row of the figure), each offspring will have received one allele by chance from both parents, and (with large numbers of offspring) the ratio of colours would be 1 orange to 1 white. When two orange heterozygous Ww tigers are mated – such as two of the grandchildren of Mohan and Begum, Ramana and Ramani, were – their offspring will be in a 1-2-1 genetic ratio (WW, 2Ww, ww), and a 3 to 1 orange to white colour ratio.

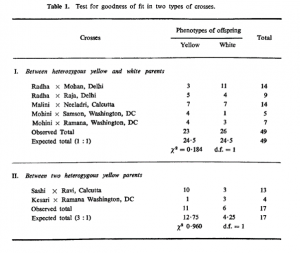

As with Mendel’s extensive pea crosses, the theoretical expectations based on a model that the white colour is recessive to orange and that alleles segregate equally can be tested against data. As the table below shows, this expectation is close to what was observed.

Indeed, more recently the causal genetic variant has been identified as one leading to a single amino acid change in the transporter protein SLC45A2 (although, as with everything in genetics, there is greater complexity hidden in the spectrum of coat colour variation within white tigers).

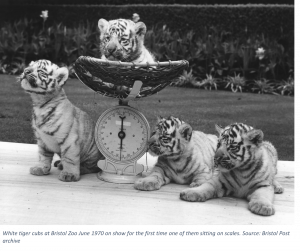

It is clear there was considerable interest in both the genetics of the captive white tigers and in their financial value. When Champak (who was male) and Chameli (who was female) arrived in Bristol in 1963 thoughts turned quickly to their potential offspring. Chameli produced three litters – all white, of course – of 14 cubs in all. All four of the first litter died soon after birth and one of the second litter also died young and was devoured by Chameli. The third litter (see the photograph below, with growth monitoring perhaps being illustrated) also prefigured an unhappy story, of generally short lives. Indeed, one of the five was already dead by the time this early photograph was taken. Something was clearly amiss, and it was not anything specific to Bristol.

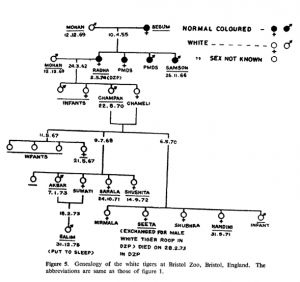

The reason for the poor health of the white tigers is not to do with the single amino acid change, but rather with the extreme inbreeding which was employed to extend the highly profitable white tiger lineage. The first cubs – including Champak and Chameli in Bristol – were a result of a father-daughter mating, and were siblings who were subsequently mated. Ramana and Ramani (mentioned above) were also both grandchildren of the same grandparents, whilst also being siblings. This inbreeding led to high mortality and congenital facial, eye, gastrointestinal tract, cardiac, kidney and other conditions. This was recognised early, and in the Bristol Zoo genealogy (below) the reason Seeta was exchanged for the white tiger Roop from the Delhi Zoological Park (where I witnessed many white tigers when living in the city in 2009 and 2010) was both to generate a better sex balance and in an effort to reduce the extent of inbreeding.

There has also been the suggestion that inbreeding has led to white tigers being more aggressive (perhaps from perceptual difficulties and stemming from fear). High-profile stories, such as when the white tiger Jupiter killed Chuck Lizza and Joy Holliday of “Cat Dancers” (an exotic tiger entertainment act), and the even more sensational story of the white tiger Montecore (which apparently translates into “maneater”) nearly killing Roy Horn of Las Vegas megastars Siegfried and Roy certainly raised the profile of this possibility (although in the latter case it is difficult to believe anything about the story). However the apparently innocent play below might be less benign than it looks.

As the news of the poor health due to inbreeding suffered by the white tigers became more widely known, their visitor attraction fell, and by mid-1985 they were gone from the Bristol Zoo collection. The inbreeding and display of the white tigers would certainly not fit with the ethos of the zoo (advanced in 2008) to “maintain and defend biodiversity through breeding endangered species, conserving threatened species and habitats and promoting a wider understanding of the natural world”.

Sadly, the Bristol Zoo Gardens site closed its doors to the public later in the summer of 2022. All the animals and activities are moving to the much-bigger Wild Place site in South Gloucestershire. This newer site has been purpose built with the zoo’s conservation goals at its heart, but it will be sad to say goodbye to the zoo that has been in the heart of Clifton in Bristol for nearly two centuries.

Find out more information about the conference here. This post has been updated after the conference.

Note: Andrew Flack’s excellent book on Bristol Zoo, “The Wild Within: Histories of a Landmark British Zoo. 2018, Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press” alerted me to the story of the white tigers in Bristol Zoo.

Nice one, George.

I saw the stunning white tigers at the zoo a few times in 1976+

Didn’t know about the inbreeding and poor survival history.

Cheers.