Back in May, IEU researcher Dr Gemma Sharp took part in Creative Reactions, an initiative that pairs scientists with artists to create artwork based on their academic research. With 50 artists and 50 scientists collaborating on works from sculptures and wood carvings to canvas, digital and performance art, the 2019 exhibition ran across two venues in Bristol.

Gemma was paired with Olga Trevisan, an artist based in Venice, Italy. They had conversations over Skype where they spoke about their work and formed some initial ideas about how they could combine their interests in a new way while remaining coherent to their own practices. Reflecting on the collaboration, Olga said, “I love how curious you can be of a subject you haven’t considered before. I believe collaboration helps to open your own mind.”

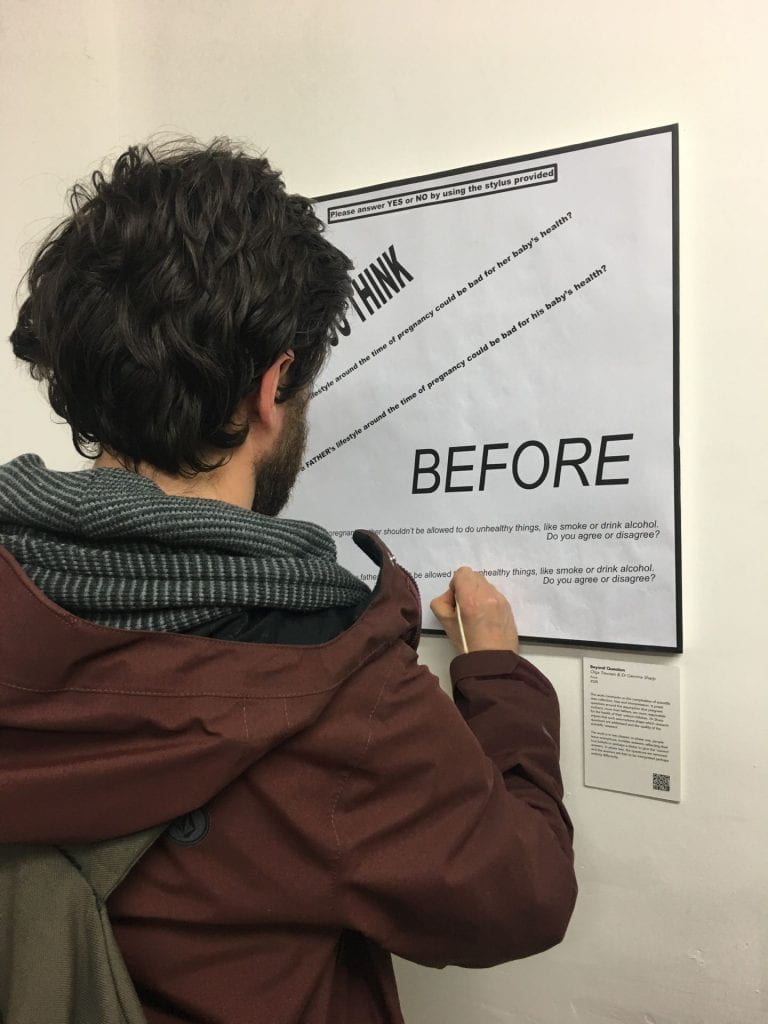

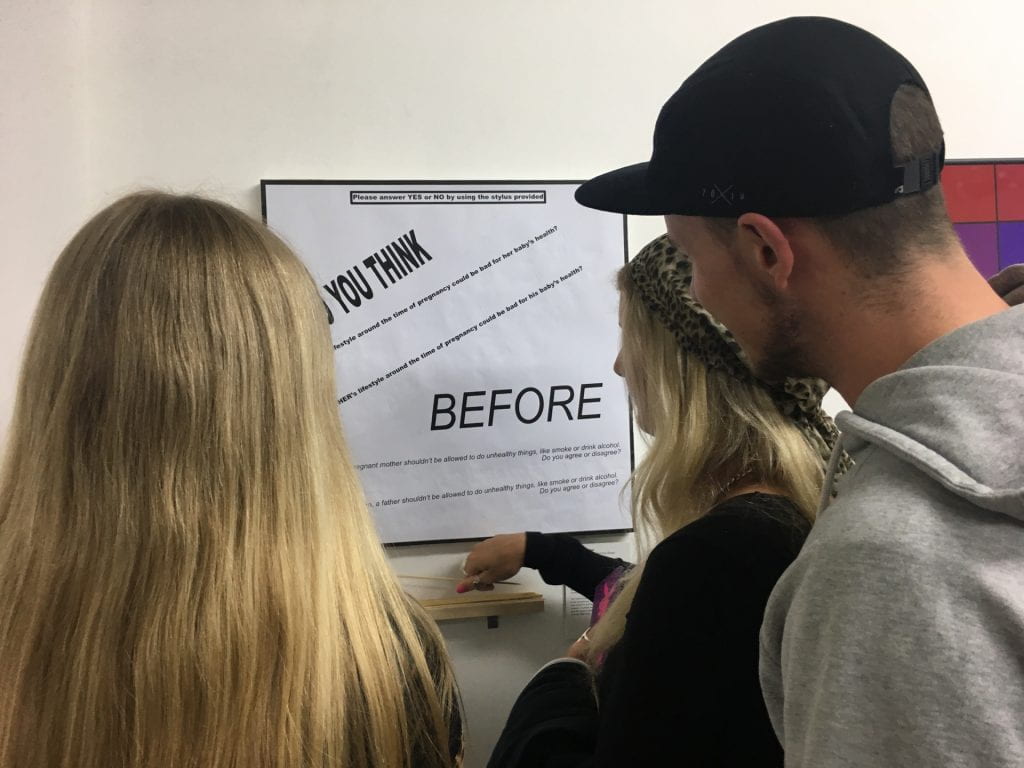

Based on some of the work around EPoCH, Olga created a piece called Beyond Question, which comments on the complexities of scientific data collection, bias and interpretation.

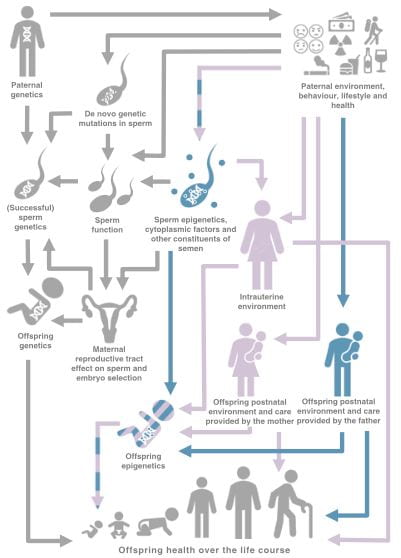

It poses questions around the pervasive assumption that pregnant women are more responsible for the (ill) health of their unborn children than their male partners are. Gemma and colleagues have argued that such assumptions drive the research agenda and the public perception of parental roles, by shaping which research questions get asked, which data are collected, and the quality of the scientific ‘answer’.

Beyond Question was presented in two phases at two separate exhibitions: during the first phase, people were invited to answer questions with a simple Yes or No using a stylus; leaving no marks but only invisible, anonymous traces on the surface below. Answers will reflect the real assumptions, beliefs and attitudes of the respondent, but perhaps also, despite anonymity, their eagerness to ‘please’ the questioners, to give the ‘right’ answer, and to mask their true responses to paint themselves in the ‘best’ light.

In the second phase, the questions were removed and the answer traces were left alone to carry their own meaning; free to be combined with the attitudes, beliefs and assumptions of the viewer and to be interpreted and judged in perhaps an entirely different way.

The questions posed were:

- “Do you think a mother’s lifestyle around the time of pregnancy could be bad for her baby’s health?”

- “Do you think a father’s lifestyle around the time of pregnancy could be bad for his baby’s health?”

- “Before her baby is born, a pregnant mother shouldn’t be allowed to do unhealthy things, like smoke or drink alcohol. Do you agree or disagree?”

- “Before his baby is born, a father shouldn’t be allowed to do unhealthy things, like smoke or drink alcohol. Do you agree or disagree?”

Find out more

Further info about Creative Reactions Bristol is available on their facebook page, or contact Matthew Lee on matthew.lee@bristol.ac.uk