Professor Paul Cairney, University of Stirling

Dr John Boswell, University of Southampton

Richard Gleave, Deputy Chief Executive and Chief Operating Officer, Public Health England

Dr Kathryn Oliver, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

The Green Paper on preventing ill health was published earlier this week, and many have criticised that proposals do not go far enough. Our guest blog explores some of the challenges that Public Health England face in providing evidence-informed advice. Read on to discover the reflections from a recent workshop on using evidence to influence local and national strategy and their implications for academic engagement with policymakers.

On the 12th June, at the invitation of Richard Gleave, Professor Paul Cairney and Dr John Boswell led a discussion on ‘institutionalising’ preventive health with senior members of Public Health England (PHE).

It follows a similar event in Scotland, to inform the development of Public Health Scotland, and the PHE event enjoyed contributions from key members of NHS Health Scotland.

Cairney and Boswell drew on their published work – co-authored with Dr Kathryn Oliver and Dr Emily St Denny (University of Stirling) – to examine the role of evidence in policy and the lessons from comparable experiences in other public health agencies (in England, New Zealand and Australia).

This post summarises their presentation and reflections from the workshop (gathered using the Chatham House rule).

The Academic Argument

Governments face two major issues when they try to improve population health and reduce health inequalities:

- Should they ‘mainstream’ policies – to help prevent ill health and reduce health inequalities – across government and/ or maintain a dedicated government agency?

- Should an agency ‘speak truth to power’ and seek a high profile to set the policy agenda?

Our research provides three messages to inform policy and practice:

- When governments have tried to mainstream ‘preventive’ policies, they have always struggled to explain what prevention means and reform services to make them more preventive than reactive.

- Public health agencies could set a clearer and more ambitious policy agenda. However, successful agencies keep a low profile and make realistic demands for policy change. In the short term, they measure success according to their own survival and their ability to maintain the positive attention of policymakers.

- Advocates of policy change often describe ‘evidence based policy’ as the answer. However, a comparison between (a) specific tobacco policy change and (b) very general prevention policy shows that the latter’s ambiguity hinders the use of evidence for policy. Governments use three different models of evidence-informed policy. These models are internally consistent but they draw on assumptions and practices that are difficult to mix and match. Effective evidence use requires clear aims driven by political choice.

Overall, they warn against treating any response – (a) the idiom ‘prevention is better than cure’, (b) setting up a public health agency, or (c) seeking ‘evidence based policy’ – as a magic bullet.

Major public health changes require policymakers to define their aims, and agencies to endure long enough to influence policy and encourage the consistent use of models of evidence-informed policy. To do so, they may need to act like prevention ninjas, operating quietly and out of the public spotlight, rather than seeking confrontation and speaking truth to power.

The Workshop Discussion

The workshop discussion highlighted an impressive level of agreement between the key messages of the presentation and the feedback from most members of the PHE audience.

One aspect of this agreement was predictable, since Boswell et al’s article describes PHE as a relative success story and bases its analysis of prevention ‘ninjas’ on interviews with PHE staff.

However, this strategy is subject to frequent criticism. PHE has to manage the way it communicates with multiple audiences, which is a challenge in itself. One key audience is a public health profession in which most people see their role as to provoke public debate, shine a light on corporate practices (contributing to the ‘commercial determinants of health’), and criticise government inaction. In contrast, PHE often seeks to ensure that quick wins are not lost, must engage with a range of affected interests, and uses quiet diplomacy to help maintain productive relationships with senior policymakers. Four descriptions of this difference in outlook and practice stood out:

- Walking the line. Many PHE staff gauge how well they are doing in relation to the criticism they receive. Put crudely, they may be doing well politically if they are criticised equally by proponents of public health intervention and vocal opponents of the ‘nanny state’.

- Building and maintaining relationships. PHE staff recognise the benefit of following the rules of the game within government, which include not complaining too loudly in public if things do not go your way, expressing appreciation (or at least a recognition of policy progress) if they do, and being a team player with good interpersonal skills rather than simply an uncompromising advocate for a cause. This approach may be taken for granted by interest groups, but tricky for public health researchers who seek a sense of critical detachment from policymakers.

- Managing expectations. PHE staff recognise the need to prioritise their requirements from government. Phrases such as ‘health in all policies’ often suggest the need to identify a huge number of crucial, and connected, policy changes. However, a more politically feasible strategy is to identify a small number of discrete priorities on which to focus intensely.

- Linking national and local. PHE staff who work closely with local government, the local NHS, and other partners, described how they can find it challenging to link ‘place-based’ and ‘national policy area’ perspectives. Local politics are different from national politics, though equally important in implementation and practice.

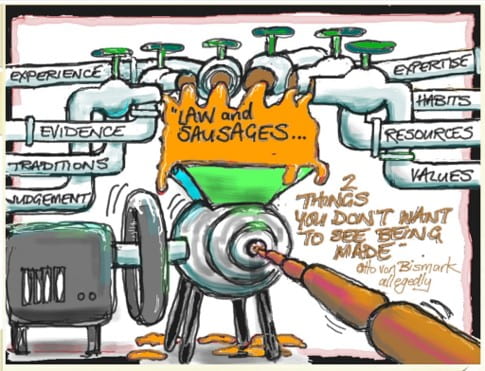

There was also high agreement on how to understand the idea of ‘evidence based’ or ‘evidence informed’ policymaking (EBPM). Most aspects of EBPM are not really about ‘the evidence’. Policy studies often suggest that, to improve evidence use requires advocates to:

- find out where the action is, and learn the rules and language of debate within key policymaking venues, and

- engage routinely with policymakers, to help them understand their audience, build up trust based on an image of scientific credibility and personal reliability, and know when to exploit temporary opportunities to propose policy solutions.

- To this we can add the importance of organisational morale and a common sense of purpose, to help PHE staff operate effectively while facing unusually high levels of external scrutiny and criticism. PHE staff are in the unusual position of being (a) part of the meetings with ministers and national leaders, and (b) active at the front-line with professionals and key publics.

In other words, political science-informed policy studies, and workshop discussions, highlighted the need for evidence advocates to accept that they are political actors seeking to win policy arguments, not objective scientists simply seeking the truth. Scientific evidence matters, but only if its advocates have the political skills to know how to communicate and when to act.

Although there was high agreement, there was also high recognition of the value of internal reflection and external challenge. In that context, one sobering point is that, although PHE may be relatively successful now (it has endured for some time), we know that government agencies are vulnerable to disinvestment and major reform. This vulnerability underpins the need for PHE staff to recognise political reality when they pursue evidence-informed policy change. Put bluntly, they often have to strike a balance between two competing pressures – being politically effective or insisting on occupying the moral high ground – rather than assuming that the latter always helps the former.

This blog post was originally published on the PolicyBristol blog.