Dr Laura Howe

Prof Debbie Lawlor

Dr Lindsey Pike

Follow Alisha, Laura, Debbie and Lindsey on Twitter

Policy engagement is becoming more of a priority in academic life, as emphasis shifts from focusing purely on academic outputs to creating impact from research. Research impact is defined by UKRI as ‘the demonstrable contribution that excellent research makes to society and the economy’.

On 25 June 2019 the IEU held its first Engagers’ Lunch event, which focused on policy engagement. Joined by Dr Alisha Davies, Head of Research from Public Health Wales, Dr Laura Howe, Professor Debbie Lawlor and Dr Lindsey Pike from the IEU facilitated discussion drawing on their experiences – from both sides of the table – of connecting research and policy. Below we summarise advice from our speakers about engaging with policy.

The benefits of engaging with policy & how to do it

- As an academic you need to consider what your ‘offer’ is. What expertise do you bring? This may be topic specific knowledge or relate to strong academic skills such as critical approaches to complex challenges, novel methods in evaluation, health economics. Recognise where you add value; the remit of academia is to develop robust evidence in response to complex and challenging questions using reliable methods – a gap that those in practice and /or policy cannot fill alone.

- Find the right people to engage with – who are the decision makers in your area of research? Listen to what is currently important to inform action / policy. Read through local and national strategies in your topic of expertise to understand the wider landscape and where your work might inform, or where you might be able to address some of those key gaps. Academics can also submit evidence to policy (colleagues from the University of Bristol can access PolicyBristol’s policy scan, which lists current opportunities to engage).

- Be visible and actively engage. Find out what local events are going on in your area related to your research and go along to meet local public health professionals. It’s a good way to meet people, find commonalities and form collaborations.

- Condense your new research into a short briefing, identify what it adds to the existing evidence base, how does it inform given the wider context.

- As an academic you will have a network of other research colleagues. Policymakers value being able to draw on this network for information. When providing evidence, don’t just cite your own – objectivity is one of the key advantages of working with academics, and policymakers value your intellectual independence. Your knowledge of the broader evidence base is invaluable.

- Setting up a research steering group or stakeholder panel can be a great way to develop your relationships and ensure your research is speaking to policy, practice or industry priorities. Key to this is getting the right people involved – this blog post from Fast Track Impact has some useful advice.

The challenges of engaging with policy & how to navigate them

- Academic and policymaking timescales are different. Policymakers need an answer yesterday while academics may not feel comfortable with providing a definitive response without time for reflection. There’s a need for flexibility on both sides.

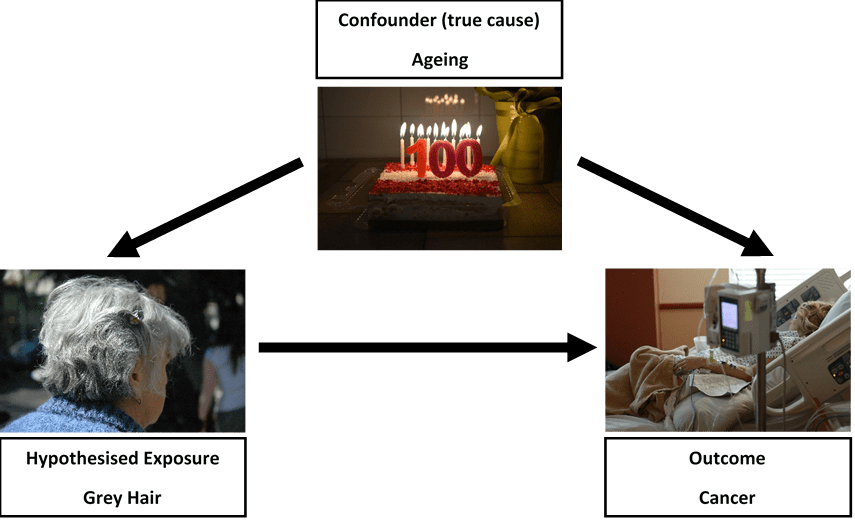

- There are also tensions between the perceived need for certainty and ability to be able to provide it. Policymakers may want ‘an answer’, but the evidence base may not be robust enough to give one. It is more useful to outline what we do and do not know, with a ‘balance of probabilities’ recommendation, than to say ‘more research is needed’.

- Language can also be a barrier. Academic language is complex and, at times, impenetrable; policymaker documents need to be aimed at an intelligent lay audience, without jargon, and focusing on what matters to them (outlining policy options and the evidence base behind them – not lengthy discussions of statistical methods). Look at Public Health Wales’ publications, for example on digital technology, adverse childhood experiences and resilience, or mass unemployment events, or examples from the NIHR Dissemination Centre or PolicyBristol to get a sense of the language to use.

- Do you think you have time for networking with non-academic stakeholders? The perception of opportunity costs can be another barrier for academics. While time for networking might not be costed into your grant funding, think of it in the same way as writing a grant application; you can’t guarantee the outcome but the potential reward is significant.

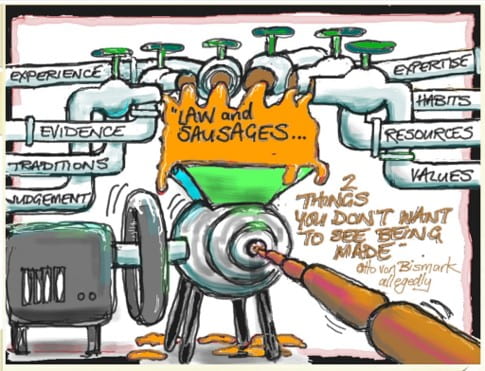

- There are no guarantees in policy engagement work, and a level of realism is required around what findings from one study can achieve. Policymaking is a complex and messy process; the evidence base is just one factor in decision making. Your recommendations may not be taken up because of politics, resource issues, or other concerns taking priority. Sometimes your relationships will reach honourable dead ends, where you realise that interests, capacity or timescales are not as aligned as you thought. Knowing this before you start is important to avoid feeling disillusioned.

In summary, the panel concluded that policymakers are interested in academic research as long as their priorities are addressed. While outcomes are not guaranteed, our colleagues at PolicyBristol advise a strategy of ‘engineered serendipity’ – looking for and capitalising on opportunities, being ready to talk about your research in a clear and policy orientated way (why does your research matter and what are the key recommendations?) and aim to build long term and trusting relationships with policymakers.

If you’d be interested in attending a future Engagers’ Lunch, please contact Lindsey Pike.

Further information & resources

PolicyBristol aims to enhance the influence and impact of research from across the University of Bristol on policy and practice at the local, national and international level.

Public Health Wales Research and Evaluation work collaboratively across Public Health Wales and with external academic and partner organisations, and are keen to facilitate research links across Public Health Wales with new national and international partners.

Research impact at the UK Parliament ‘Everything you need to know to engage with UK Parliament as a researcher’

Parliamentary research services across the legislatures include:

- House of Commons Library: an independent research and information unit. It provides impartial information for Members of Parliament of all parties and their staff.

- Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology: Parliament’s in-house source of independent, balanced and accessible analysis of public-policy issues related to science and technology.

- Research and Information Service (RaISe): aims to meet the information needs of the Northern Ireland Assembly Members, their staff and the secretariat in an impartial, objective, timely and non-partisan manner.

- Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe): the internal parliamentary research service for Members of the Scottish Parliament.

- Senedd Research: an expert, impartial and confidential research and information service designed to meet the needs of Wales’ National Assembly Members and their staff.