Dr Gemma Sharp, University of Bristol

For many years, researchers have been studying how our early life experiences, including those that happen before we are born, can affect our lifelong health. In an article we wrote last year, Debbie Lawlor (University of Bristol), Sarah Richardson (Harvard University) and I show that most of these studies have focused on the characteristics and behaviours of mothers around the time of pregnancy. In a recent paper published in the Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, Debbie Lawlor, Sarah Richardson, Laura Schellhas and I show that there have been more studies of maternal prenatal influences on offspring health than any other factors (read more here).

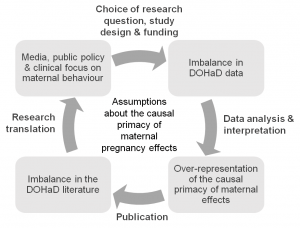

We argue this is because people assume that mothers, through their connection to the developing fetus in the womb, are the single most important factor in shaping a child’s health. This assumption runs deep and is reinforced at every level, from researchers, to research funders, to journalists, to policy makers, to health care professionals and the general public (see figure 1).

In our article, we question the truth behind this assumption.

Is there a strong scientific rationale for studying pregnant mothers so intensively?

Well, no actually. Although a lot of studies have found correlations between maternal characteristics and offspring health, the evidence that these characteristics actually have a causal effect is pretty weak. And since there haven’t been many studies of the effects of fathers and other factors, it’s difficult to say how important any maternal effect might be compared to any other early life experience.

Focusing so intensively on pregnant mothers, and interpreting all evidence as causal (if a mother does X, their unborn child will have Y), can have very damaging effects. Complex, nuanced scientific findings are being rushed into simplified advice that, although well-meaning, places the burden of blame on individual pregnant women. For example, there has been very little research on the effects of low-level drinking during pregnancy, but the current advice in the United States is for all sexually active women of reproductive age to avoid alcohol completely if they are not using birth control, for fear of fetal harm.

A culture of blame

The culture of blame is more overt in the media, where articles are often guilty of scaremongering. This feeds into public beliefs about how pregnant women should and shouldn’t behave, which can limit pregnant women’s freedom and even lead to questions around whether their behaviour is criminal. For example, pregnant women have reportedly been refused alcoholic drinks in bars, and taking drugs during pregnancy is legally classed as child abuse in many US states.

In our article, we make a number of recommendations that we hope will create more of a balance. In particular, we call for more research on how child health might be influenced by fathers and other factors, including the social conditions and inequalities that influence health behaviours. We also call for greater attention to be paid to how health advice to pregnant women is constructed and conveyed, with clear communication of the supporting scientific evidence to allow individuals to form their own opinions.

The EPoCH study

In June, I’ll begin work on a new project to investigate how both mothers and fathers’ lifestyles might causally affect the health of their children. Funded by the Medical Research Council, the EPoCH (Exploring Prenatal influences on Childhood Health) study will highlight whether attempts to improve child health are best targeted at mothers, fathers or both parents. I’m excited to work closely with the people behind WRISK to help ensure that findings from this project are communicated effectively and responsibly.

I hope that, along with the rest of the research community, we can produce high quality evidence to support health care and advice that maximises the health of all family members and stops blaming women for the ill health of the next generation.

The original article can be accessed (open access) here, and the authors’ full list of recommendations can be found below.

Full recommendations

Our full recommendations, which apply variously to researchers, journalists, policy makers and clinicians:

- Collect more and better quality data on partners of pregnant women.

- In addition to studying the effects of mothers, study and compare the effects of partners/fathers, social and other factors on child health.

- Look for causal relationships between these factors and child health, not just (potentially spurious) correlations.

- Publish all results, including negative results, to give a balanced view of the evidence.

- Be aware and critical of the current imbalance in the scientific literature and how this will bias our overall understanding of the truth.

- Collaborate with social scientists to consider the social implications of this research and the role of cognitive bias and social assumptions when interpreting findings.

- When communicating findings, put the risk in context: compare findings to the broader scientific literature and the social environment.

- Avoid language that suggests individual mothers are responsible for direct harm to their foetuses (most of the evidence will be based on averages in a population and can’t be assumed to apply to all individuals).

- Where there is evidence of a paternal effect, aim public health advice at both parents.

- Explain the level of risk in a way that empowers people to assess the evidence and form their own opinions (i.e. avoid over simplification).

This blog post is an edited version of one originally posted on the WRISK project website.