Drs Luisa Zuccolo and Cheryl McQuire, Department of Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol.

The problem

Soon after the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11th 2020, the UN declared the start of an infodemic, highlighting the danger posed by the fast spreading of unchecked misinformation. Defined as an overabundance of information, including deliberate efforts to disseminate incorrect information, the COVID-19 infodemic has exacerbated public mistrust and jeopardised public health.

Social media platforms remain a leading contributor to the rapid spread of COVID-19 misinformation. Despite urgent calls from the WHO to combat this, public health responses have been severely limited. In this project, we took steps to begin to understand and address this problem.

We believe that it is imperative that public health researchers evolve and develop the skills and collaborations necessary to combat misinformation in the social media landscape. For this reason, in Autumn 2020 we extended our interest in public health messaging, usually around promoting healthy behaviours during pregnancy, to study COVID-19 misinformation on social media.

We wanted to know:

What is the nature, extent and reach of misinformation about face masks on Twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic?

To answer this question we aimed to:

- Upskill public health researchers in the data capture and analysis methods required for social media data research;

- Work collaboratively with Research IT and Research Software Engineer colleagues to conduct a pilot study harnessing social media data to explore misinformation.

The team

Dr Cheryl McQuire got the project funded and off the ground. Dr Luisa Zuccolo led it through to completion. Dr Maria Sobczyk checked the data and analysed our preliminary data. Research IT colleagues, led by Mr Mike Jones, helped to develop the search strategy and built a data pipeline to retrieve and store Twitter data using customised application programming interfaces (APIs) accessed through an academic Twitter account. Research Software Engineering colleagues, led by Dr Christopher Woods, provided consultancy services and advised on the analysis plan and technical execution of the project.

Cheryl McQuire, Luisa Zuccolo, Maria Sobcyzk, Mike Jones, Christopher Woods. (Left to Right)

Too much information?!

Initial testing of the Twitter API showed that keywords, such as ‘mask’ and ‘masks’, returned an unmanageable amount of data, and our queries would often crash due to an overload of Twitter servers (503-type errors). To address this, we sought to reduce the number of results, while maintaining a broad coverage of the first year of the pandemic (March 2020-April 2021).

Specifically, we:

I) Searched for hashtags rather than keywords, restricting to English language.

II) Requested original tweets only, omitting replies and retweets.

III) Broke each month down into its individual days in our search queries to minimise the risk of overload.

IV) Developed Python scripts to query the Twitter API and process the results into a series of CSV files containing anonymised tweets, metadata and metrics about the tweets (no. of likes, retweets etc.), and details and metrics about the author (no. of followers etc.).

V) Merged data into a single CSV file with all the tweets for each calendar month after removing duplicates.

What did we find?

Our search strategy delivered over three million tweets. Just under half of these were filtered out by removing commercial URLs and undesired keywords, the remaining 1.7m tweets by ~700k users were analysed using standard and customized R scripts.

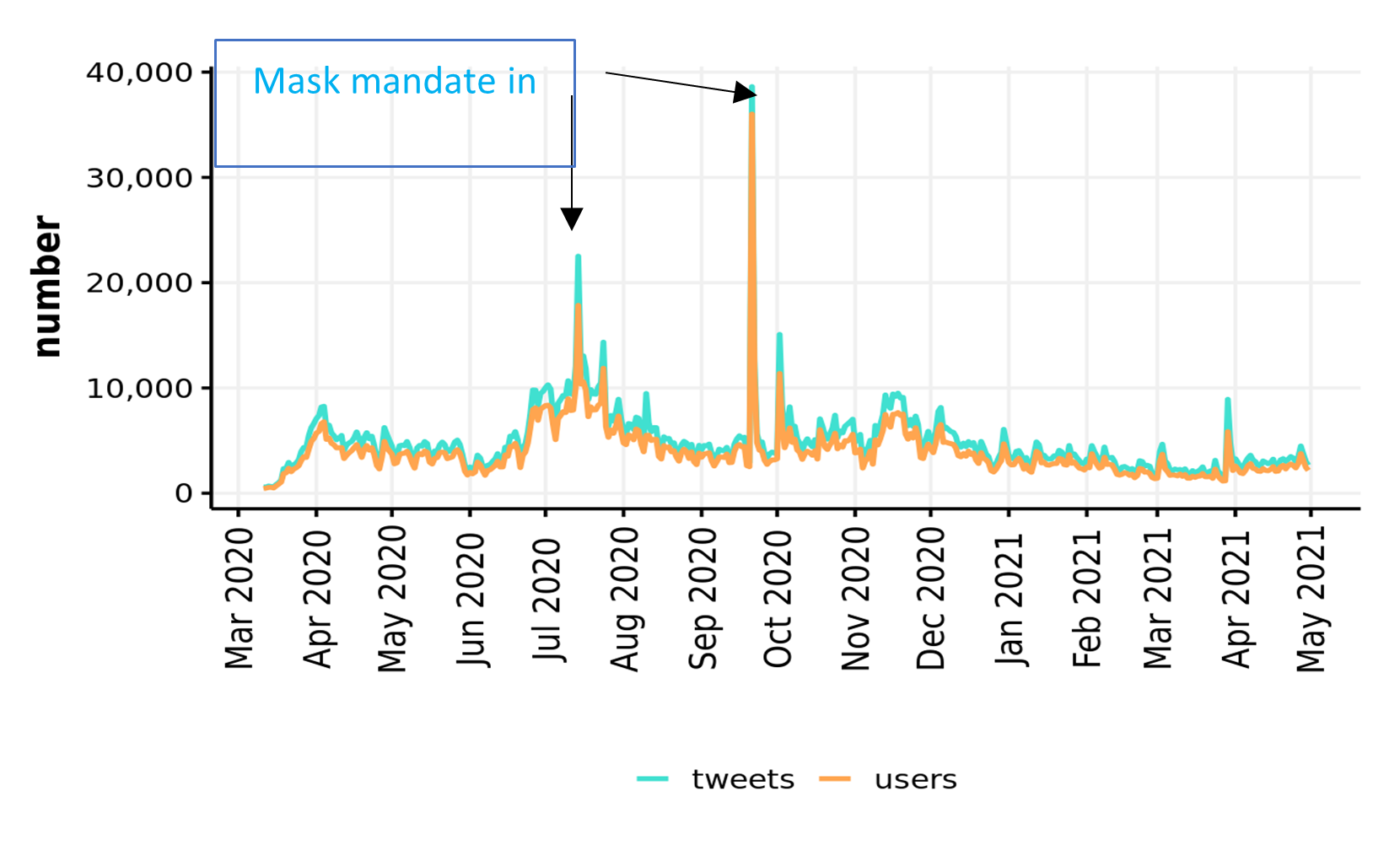

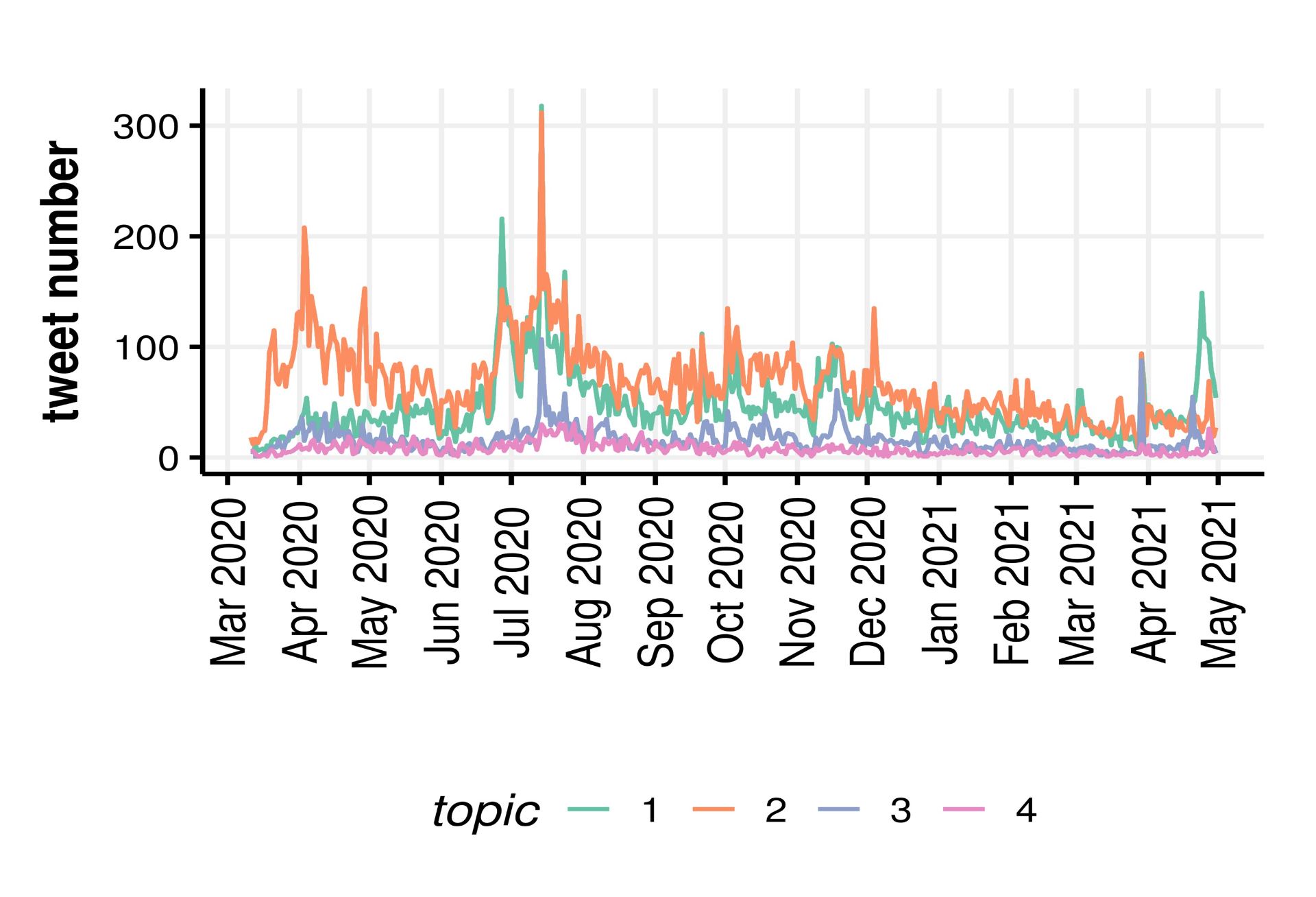

First, we used unsupervised methods to describe any and all Twitter activity picked up by our broad searches (whether classified as misinformation or not). The timeline of this activity revealed clear peaks around the UK-enforced mask mandates in June and September 2020.

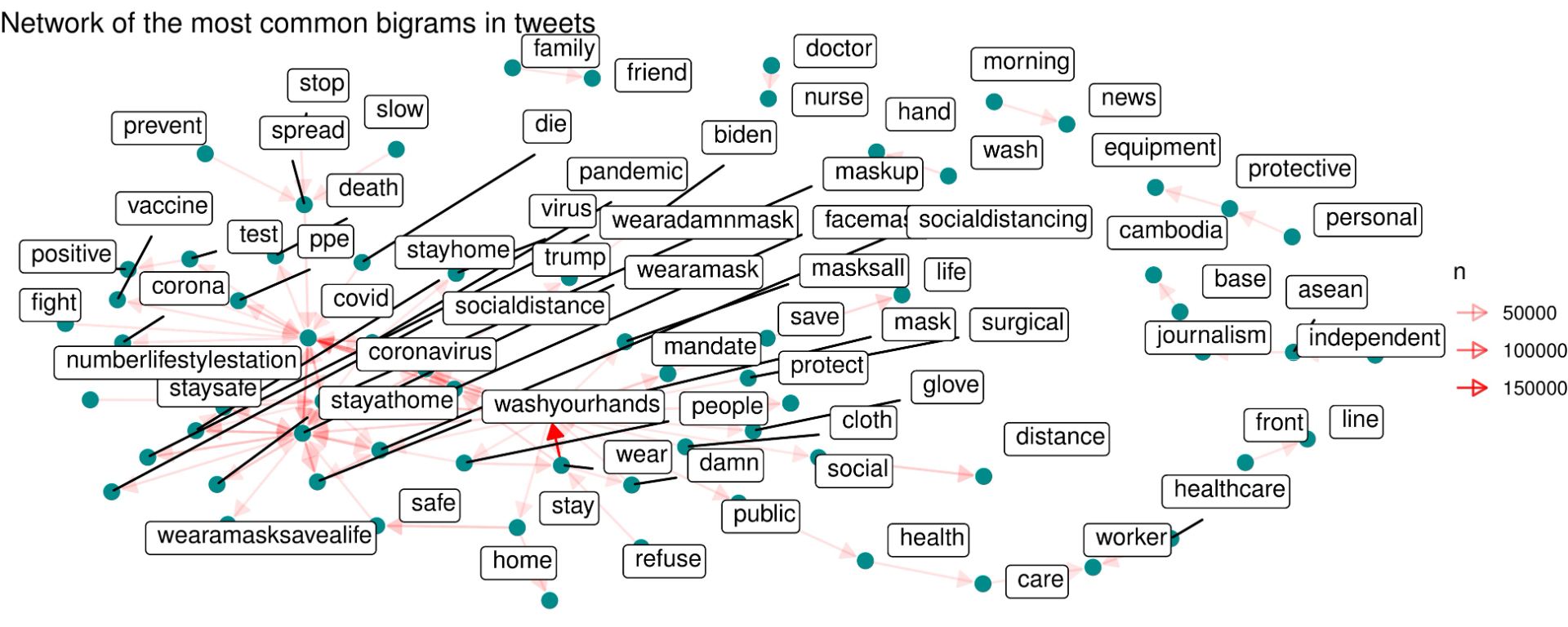

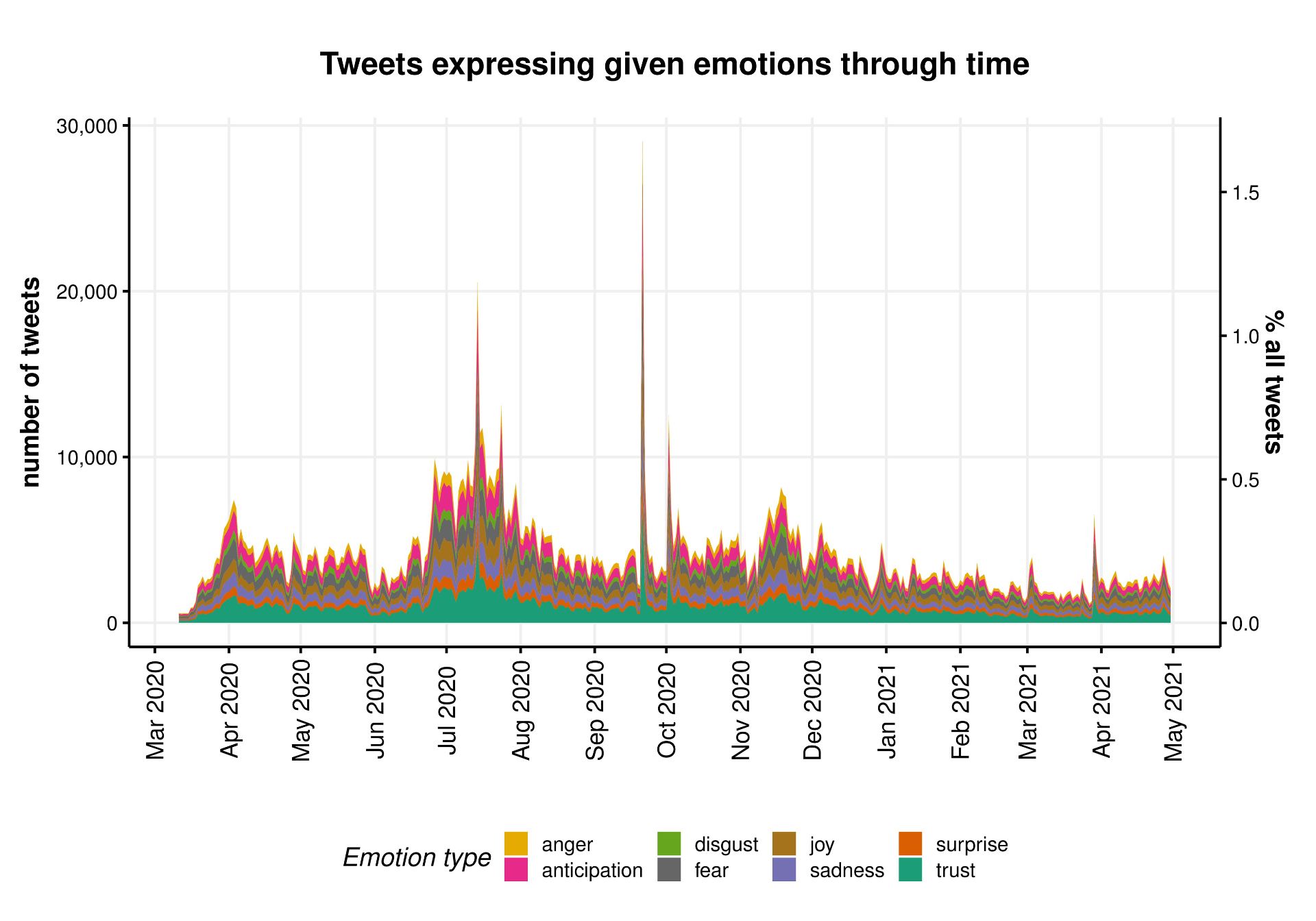

We further described the entire corpus of tweets on face masks by mapping the network of its most common bigrams and performing sentiment analysis.

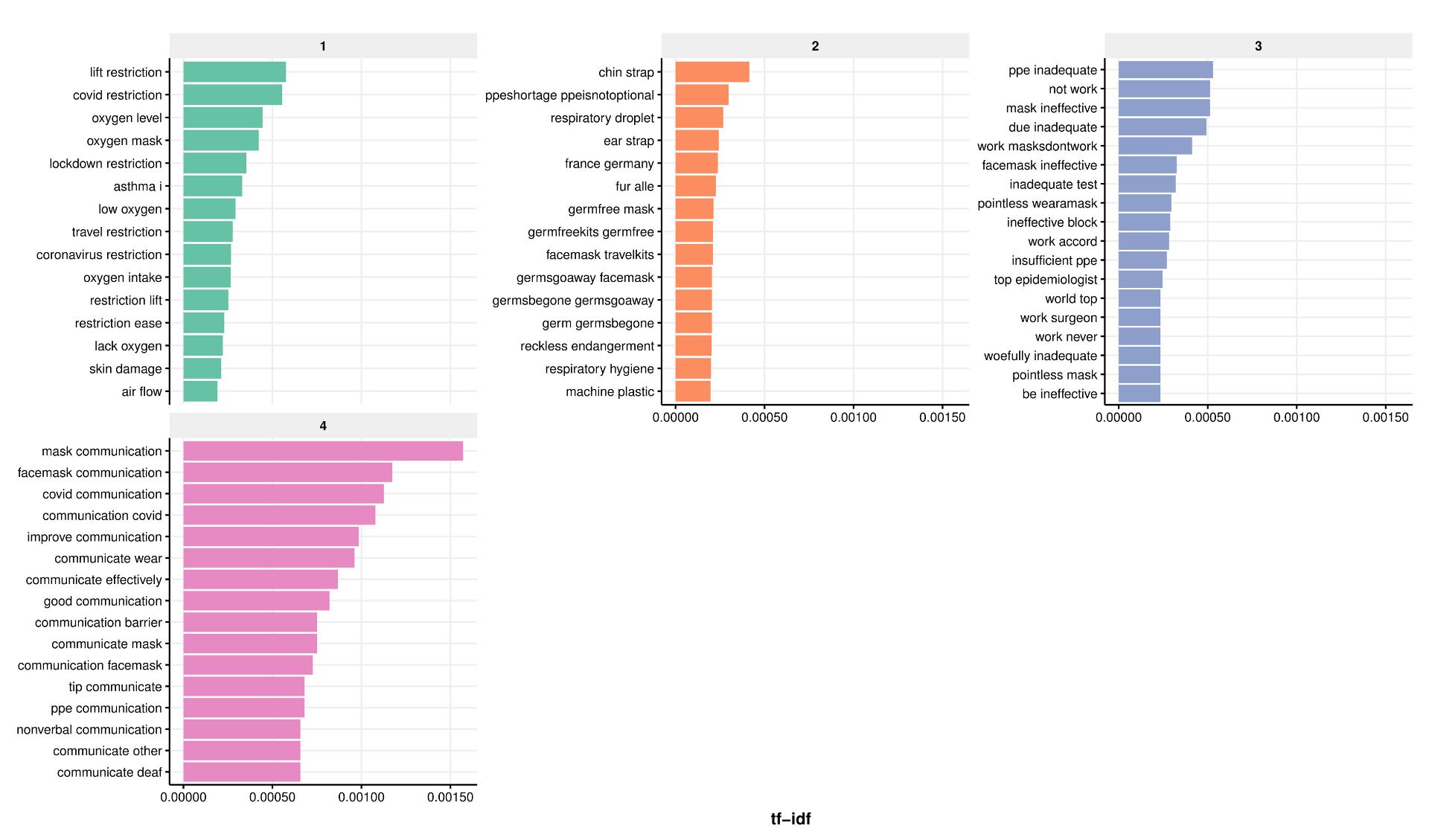

We then quantified the nature and extent of misinformation through topic modelling, and used simple counts of likes to estimate the reach of misinformation. We used semi-supervised methods including manual keyword searches to look for established types of misinformation such as face masks restricting oxygen supply. These revealed that the risk of bacterial/fungal infection was the most common type of misinformation, followed by restriction of oxygen supply, although the extent of misinformation on the risks of infection decreased as the pandemic unfolded.

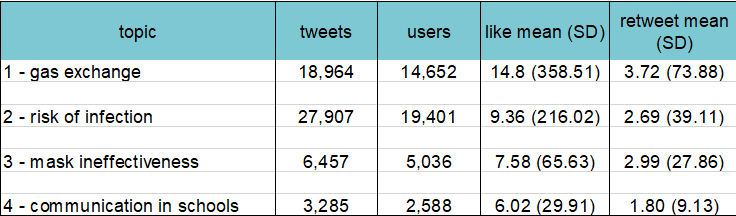

Extent of misinformation (no tweets), according to its nature: 1- gas exchange/oxygen deprivation, 2- risk of bacterial/fungal infection, 3- ineffectiveness in reducing transmission, 4- poor learning outcomes in schools.

Relative to the volume of tweets including the hashtags relevant to face masks (~1.7m), our searches uncovered less than 3.5% unique tweets containing one of the four types of misinformation against mask usage.

A summary of the nature, extent and reach of misinformation on face masks on Twitter – results from manual keywords search (semi-supervised topic modelling).

A more in-depth analysis of the results attributed to the 4 main misinformation topics by the semi-supervised method revealed a number of potentially spurious topics. Refinements of these methods including iterative fine-tuning were beyond the scope of this pilot analysis.

Our initial exploration of Twitter data for public health messaging also revealed common pitfalls of mining Twitter data, including the need for a selective search strategy when using academic Twitter accounts, hashtag ‘hijacking’ meaning most tweets were irrelevant, imperfect Twitter language filters and ads often exploiting user mentions.

Next steps

We hope to secure further funding to follow-up this pilot project. By expanding our collaboration network, we aim to improve the way we tackle misinformation in the public health domain, ultimately increasing the impact of this work. If you’re interested in health messaging, misinformation and social media, we would love to hear from you – @Luisa_Zu and @cheryl_mcquire.

Note:

This blog post was original written for the Jean Golding Institute blog