PhD student Maddy Smith shares what she learned from attending a recent international conference on diabetes research.

An exciting time for metabolic health

Weight loss drugs such as Wegovy and Ozempic have made many headlines and sparked a frenzy on social media in recent months. Not only is their potential to “end obesity” being unpacked in the media, but also their issues such as side effects, weight regain after stopping taking it, and supply shortages. Since obesity is a main risk factor for type 2 diabetes, these new drugs have implications for diabetes treatment – in fact, some of them were originally developed to treat diabetes and weight loss was noticed to be a concurrent effect.

The work behind the headlines

Behind the provocative headlines, a myriad of in-depth studies is taking place across the world with the aim of understanding how well these drugs (and other interventions) actually work, how long for and how safe they are for long-term use. Researchers working across disciplines including epidemiology, molecular biology and primary care are collaborating to uncover the science behind preventing and treating diabetes.

I recently attended EASD 2023, the annual conference for the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, in Hamburg, Germany. As a final year PhD student researching the biological impact of weight loss interventions for obesity, the conference was an opportunity for me to encounter the breadth of diabetes-related research and its impact on treatment of the disease.

Conferences like EASD provide a platform for this research to be heard and discussed. They serve as an interface between discovery science and clinical practice and are often where key discussions take place that will move the field forward. For researchers like me it can be really energising to be surrounded by others working towards the same goal – in this case, treating diabetes.

Heading to Hamburg

Reading through the extensive conference programme the week before EASD was initially a little daunting, as there were up to eight parallel sessions scheduled at any one time across the four days. However, any apprehension soon became excitement as I identified many sessions that piqued my interest and lots of well-known names in the field.

Presenting my work

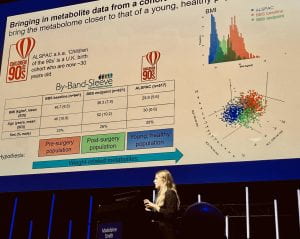

I presented my work on day one in a session curiously titled ‘Towards curing obesity’. My talk described how I have used metabolomics data from samples collected during two clinical trials of two different weight loss interventions – weight loss surgery and low-calorie meal replacements – in an attempt to move towards understanding the effect of weight loss on metabolic health.

I presented my work on day one in a session curiously titled ‘Towards curing obesity’. My talk described how I have used metabolomics data from samples collected during two clinical trials of two different weight loss interventions – weight loss surgery and low-calorie meal replacements – in an attempt to move towards understanding the effect of weight loss on metabolic health.

Bringing together this work into a 10-minute slide deck was a great opportunity for me to zoom out from the day-to-day minutia of doing such a study and consider the potential real-world impact of the research, reminding myself why this work is so important. And, of course, the public-speaking experience was invaluable – the size of the hall and the bright lights were rather nerve-wracking, not to mention the wealth of knowledge and experience in the audience!

My abstract is published online for those interested in the work I presented.

A debate to remember

Already in the mindset of real-world application following my presentation, a highlight from day two for me was a debate on whether lasting remission of type 2 diabetes is feasible in the real world. First, we heard from Professor Roy Taylor who was arguing yes, it is feasible. Prof. Taylor is one of the principal investigators for the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial, a study that has shown that patients can reverse their type 2 diabetes by following a total diet replacement programme (low-calorie soups and shakes instead of meals) to lose weight.

Up against Prof. Taylor was Professor Kamlesh Khunti who began his case by asking the audience to raise their hand if they would willingly undergo 12 weeks of total diet replacement if they had type 2 diabetes. A few hands went up, but many were retracted once Prof. Khunti pointed out that Christmas was only 11 weeks away…

Joking aside, I found the debate very thought-provoking. What strength of evidence that an intervention works (in a real-world setting) should be required before we can expect patients to undertake them, given that the intervention would likely disrupt their day-to-day life for a significant length of time?

Precision medicine for all

Keen for more exposure to advances in the treatment of diabetes, I began day three of the conference in a 90-minute session about precision medicine for cardiometabolic disease. This constituted three cutting-edge talks covering everything from a framework for its integration, to the role of multi-omics, to ensuring equity in its availability.

Something new to me here was understanding the difference between personalised medicine and precision medicine, the latter being viewed as a process that seeks to reduce error and improve accuracy in medical decisions and health recommendations. This is different to a completely individualised approach (personalised medicine) which is probably not feasible on a large scale for complex diseases like type 2 diabetes. This links to the ideas presented about the equity in precision medicine by Dr Shivani Misra and how failure to implement it for cardiometabolic disease in low- and middle-income countries will widen global health gaps. In fact, Dr Misra argued that countries with less-developed health-care systems are likely to obtain the greatest gains from precision medicine.

A series of papers was published in the Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology alongside this session with more detail on the framework for the integration of precision medicine in cardiometabolic disease.

Diabetes has many flavours…

On reflection, my main takeaway from the conference was that a key challenge for the treatment of diabetes and cardiometabolic disease is its heterogeneity (all patients are different, and their disease is different to the next patient’s). Overcoming this will require a greater and more diverse evidence base coupled with collaboration between policy makers, scientists and patients.