Dr Kayleigh Easey (@KayEasey), from the Bristol Medical School’s MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit at the University of Bristol, takes a look at a recent research investigating effects of drinking in pregnancy and child mental health.

Dr Kayleigh Easey (@KayEasey), from the Bristol Medical School’s MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit at the University of Bristol, takes a look at a recent research investigating effects of drinking in pregnancy and child mental health.

Whilst it’s generally known that heavy alcohol use during pregnancy can cause physical and cognitive impairments in offspring, there has been relatively limited evidence about the effects of low to moderate alcohol use. As such there have been conflicting conclusions about the potential harm of drinking in pregnancy, and debate around official guidance.

Alcohol use in pregnancy is still common with a recent meta-analysis showing over 40% of women within the UK to have drank some alcohol whilst pregnant. In 2016 the Department of Health updated their guidance advising abstinence from alcohol throughout pregnancy. This was in contrast to their previous advice of abstaining from alcohol in the first three months, but that 1-2 units of alcohol per week were not likely to cause harm. The updated guidance reflected a precautionary approach based on researcher’s advice of ‘absence of evidence not being evidence of absence’, due to the challenges faced in this area of study.

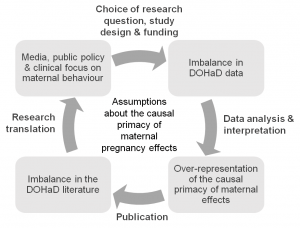

Certainly it has been challenging for researchers to determine any causal effect of alcohol use in pregnancy, particularly as the existing observational studies do not show evidence of causality. As such, caution over interpretation of results is needed given the sensitivity of alcohol as a risk factor and traditional attitudes towards low-level drinking.

Our new research sought to add to the limited body of evidence investigating causal effects, specifically on how low to moderate alcohol use could influence offspring mental health. We used data from a longitudinal birth cohort (the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children) which has followed pregnant mothers, their partners and their offspring since the 1990s, to investigate whether the frequency mothers and their partners drank alcohol during pregnancy was associated with offspring depression at age 18. We also included partner’s alcohol use in pregnancy (which is unlikely to have a direct biological effect on the developing fetus) and were able to examine if associations were likely to be causal, or due to shared confounding factors between parents such as socio-demographic factors.

We found that children whose mothers drank any alcohol at 18 weeks pregnancy may have up to a 17% higher risk of depression at age 18 compared to those mothers who did not drink alcohol. What was really interesting here is that we also investigated paternal alcohol use during pregnancy and did not find a similar association. This suggests that the associations seen with maternal drinking may be causal, rather than due to confounding by other factors (which might be expected to be similar between mothers and their partners). Many of the indirect factors that could explain the maternal effects are shared between mothers and partners (such as socio-demographic factors); despite this, we only found associations for mothers drinking.

These findings suggest evidence of a likely causal effect from alcohol consumption during pregnancy, and therefore evidence to support the updated government advice that the safest approach for alcohol use during pregnancy is for abstinence. This adds to other limited research on the effects of low level alcohol use in pregnancy. Whilst further research is needed, women can use this information to further inform their choices and help avoid risk from alcohol use both during pregnancy and as a precautionary measure when trying to conceive, as supported by the #Drymester campaign.

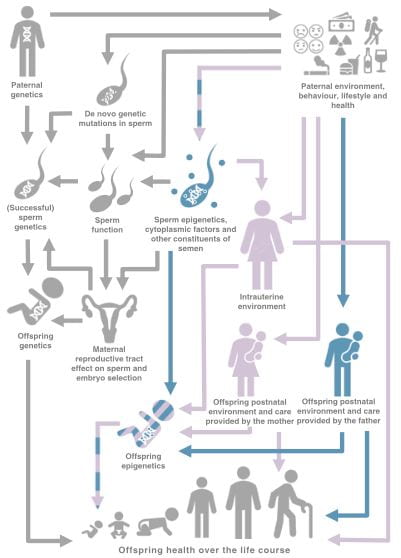

Our study highlights also the importance of including partner behaviours during pregnancy to aid in identifying causal relationships with offspring outcomes, and also because these may be important in their own right. I am currently working within the EPoCH project (Exploring Parental Influences on Childhood Health) which investigates whether and how both maternal and paternal behaviours might impact childhood health. In the meantime, it may be time for a further public health promotion highlighting that an alcohol-free pregnancy really is safer for children’s health.

This post was originally published on the Alcohol Policy blog.